Congenital/developmental

Neurodegenerative

Basics and background

The axons going to and coming from the cerebral cortex are wrapped in myelin, a very thin sheet consisting of lipids and proteins formed by oligodendrocytes. White matter refers to the pale pinkish color on macroscopy of myelinated axons.

In the white matter oligodendrocytes, astrocytes and microglial cells (and a small percentage of oligodendrocyte precursor cells) interact. The myelin is formed by oligodendrocytes and myelination is discussed below. Astrocytes are the most abundant glial cell influencing synaptic transmission and maintaining homeostasis. Astrocytes have end feet on the capillary endothelium that are part of the blood brain barrier, discussed in more detail in the “CSF spaces – glympathic system” section. Oligodendrocytes and astrocytes have a common neural progenitor. Microglial cells are derived from the yolk sac and are not only the immune cells of the brain, but also have important roles in the “recycling and renewing” of myelin.

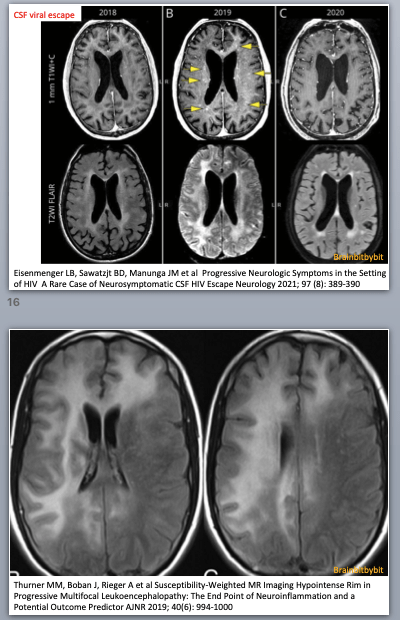

Pattern recognition on MRI is enabled by knowledge of the different cell types: E.g. in microglial pathology (HIV encephalopathy and leukodystrophies) the subcortical white matter is spared because the U fibers have low myelin turnover.

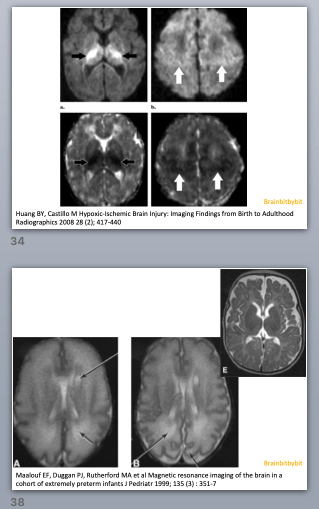

At birth the brain is largely unmyelinated. In the supratentorial brain of neonates myelinated white matter is seen only in the corticospinal tracts. In the first years of life the other axons become myelinated. The sequence of myelination is intuitive: After the corticospinal tract, the central structures including the internal capsule and corpus callosum myelinate. Then parietal (sensory), occipital (visual) and temporal lobe, and finally the frontal lobe (everybody thinks babies are cute anyway).

Figure 1 Normal myelinisation. T1w image of a term neonate (left) and T1w and T2w images of a 9 month baby (right). From an article by HM Branson: www.geiselmed.dartmouth.edu

In the first 6 months the T1 weighted image is most useful to look at myelination. Myelin is fatty and proteinacous with high T1 signal, the extracellular space between the layers of myelin around the axons is aqueous. When the child gets older the water content and T2 hyper intensity decreases and after 6 -12 months the T2 weighted image is best to assess myelination. Visually at 24 months myelination should have an adult pattern on the T1 weighted images and an almost adult pattern with only hyperintensity in the terminal zones on the T2 weighted images. However, myelination is not finished at the age of 2 years: when quantifying the T1 relaxation time, progressive shortening is measured until adulthood indicating that myelination is an ongoing process.

Myelination is driven by neural experience, which means that neurons with more electrical activity myelinate earlier (5,52). Not only does myelination increase the conduction speed, but it also prevents formation of synapses on axons that have already been myelinated. By dynamically fine-tuning the myelin thickness, its “wrapping thightness” and the distance between the nodes of Ranvier during life, the axonal conduction speed and timing of the arrival of a signal can be altered. This timing is important for simultaneous input of different brain regions and in learning. Oligodendrocytes are not just myelin forming insulators whose job is done after an axon is wrapped, but have important roles in supporting the neurons and neuronal function (50).

Oligodendrocyt precursor cells (OPC) give rise to the oligodendrocytes and these cells with replicating capacity remain present in the brain. OPCs constitute a small percentage of glial cells during life. Embryologically and in the peripartum period OPCs migrate tangentially along blood vessels in three waves from the germinal matrix to their final destination in the brain parenchyma: the first wave arises from the medial ganglionic eminence, the second from the lateral ganglionic eminence and the last wave originates from the subventricular zone. Interestingly, OPC have glutamate(13) and GABA neurotransmitter receptors, as well as dopamine receptors. These receptors are lost after differentiation into oligodendrocytes. During life from OPCs new (re)myelinating oligodendrocytes can be formed.

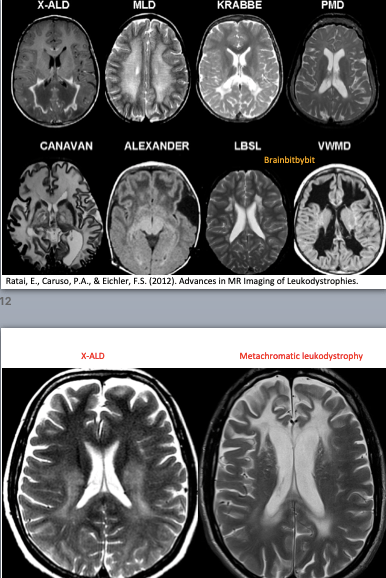

If the myelination pattern does not concur with the calender age, there can be hypomyelination or dysmyelination, meaning that not enough myelin is formed. Leukodystrophy is a term used for rare disorders involving (mainly) white matter with an underlying genetic, metabolic cause and symmetrical involvement as a key MRI finding(47-52). In demyelinating disorders there is destruction of previously formed myelin. The most known and prevalent demyelinating disease is not a leukodystrophy but an inflammatory one: multiple sclerosis, with a specific pattern of (non-symmetrical) white matter abnormalities on MRI located periventricular, in the corpus callosum, juxtacortical and infratentorial (39).

Gliomas, about one third of brain tumors, originate from glial cells in the white matter and are named after the cell they resemble and (probably) originate from, e.g. astrocytoma(59-65). These glial tumors can follow the white matter tracts with typical spreading patterns on imaging. Previous WHO classifications were mainly based on histology, but since 2016 and in the most recent 2021 classification a lot of molecular information is included. The genetics and molecular profiling will likely increase with every each new WHO classification, so this will be elucidated in the vlogs.

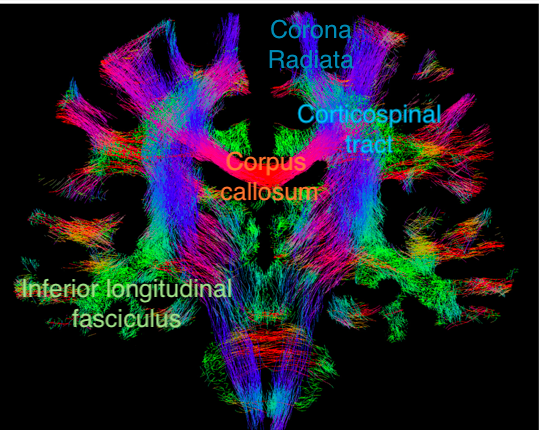

Major white matter tracts in the brain can be visualised by tractography (DTI) and can be useful in neurosurgical planning. The directions of the tracts are colour-coded: craniocaudal in blue (my mnemonic: to the sky), left-right in red (you cannot go ahead at a red light) and anterior-posterior in green (you can go ahead at a green light).

Figure 2. Coronal section showing fiber-tracking results.

Adjusted from an article by F. Calamante elucidating the pitfalls of DTI. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics9030115